Before the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) heard oral argument in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization last December, many legal scholars and commentators presumed the justices would rule for Mississippi but stop short of a wholesale reversal of Roe v. Wade. Under SCOTUS’ presumptive refashioned approach to abortion, Pro-Life laws like Mississippi’s—a 15-week ban on elective abortions—would find renewed life. But there would still be some theoretical line before which Pro-Life laws were inadmissible. The contrived constitutional right to abortion would survive, albeit in some injured form. However, under closer investigation, this presumption logically ruptures.

In Dobbs, Mississippi’s lawyers asked SCOTUS to uphold the state’s 15-week prohibition by reversing Roe in toto. They reasoned that the middle ground approaches were conceptually weaker, and that the most efficient and polished avenue to ruling for the state was to move beyond Roe. By doing so, SCOTUS would return abortion policy to the state legislatures, allowing them to regulate (or not) elective abortion befitting the political moment.

With six of nine justices appointed by Republicans, some might have understandably expected SCOTUS to target Roe at the first opportunity. All six obtained their judicial wings within the legal domain of movement conservatism, which is founded in part on opposition to Roe. All six likely believe the constitutional right to an abortion is a judicial invention with no grounding in the Constitution.

Yet, most experts thought the justices would take their time, moving in tandem with the culture. Dobbs amplified this expectation by only asking, “whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional.” Note what was not explicitly at issue in Dobbs: whether Roe is correct or whether abortion is constitutionally mandated.

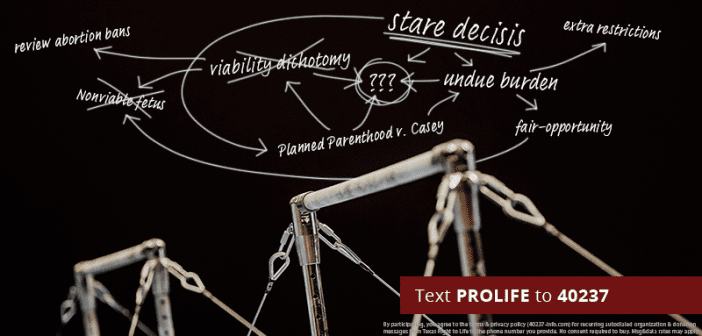

The principle by which the conservative justices of SCOTUS would uphold Roe without further entrenching abortion in their jurisprudence—something they most certainly would want to avoid—is stare decisis, which means to stand by precedent. Whether the prior decision was correct, that decision as precedent merits special respect. Stare decisis is the articulation of this principle. And the justices and advocates mentioned stare decisis some 48 times during the Dobbs oral argument.

Underneath the surface, the strength of stare decisis in Dobbs deteriorates.

Many experts have attempted to formulate a ruling that upholds Mississippi’s 15-week ban while not torpedoing Roe. All of these formulations must anchor their reasoning somewhere, and a prior SCOTUS decision naturally suits this occasion. A reworking of Planned Parenthood v. Casey must be the unmistakable basis of any stare decisis oriented decision in Dobbs.

(Casey is the 1992 SCOTUS decision that upheld Roe and established the undue burden standard and viability dichotomy. The undue burden test examines whether an abortion regulation imposes an unconstitutional restriction on a pregnant mother seeking an abortion. The viability dichotomy differentiates elective abortions before viability and those after.)

What these experts propose is that the viability dichotomy and undue burden standard are discrete modes of review with dueling purposes. They suggest that the viability dichotomy exists to review abortion bans (e.g., the Texas Heartbeat Act), while the undue burden standard governs restrictions that fall short of a ban (e.g., the Sonogram Law). If this is true, then SCOTUS can jettison the former while embracing the latter. Therefore, SCOTUS can review a ban like Mississippi’s under some interpretation of “undue burden”—most often as giving a pregnant mother a fair opportunity to obtain an abortion. Stare decisis appears to salvage a compromise.

Sherif Girgis, a law professor at Notre Dame, explains why this compromise doesn’t practically work. Most plainly, he argues, is that this reinterpretation of “undue burden” is implausible. A “fair-opportunity” reading of “undue burden” is a diachronic test that examines how a given Pro-Life law affects abortion access over time. Casey, however, uses “undue burden” in the synchronic, or momentary, sense. What matters is whether a pregnant mother can obtain an abortion at any moment under a Pro-Life law. Take this passage from Casey:

“A finding of an undue burden is a shorthand for the conclusion that a state regulation has the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.”

“Nonviable fetus” is extraneous under the “fair-opportunity” interpretation. There would be no reason to specify that undue burdens occur before viability because the “fair-opportunity” cut-off already comes sometime before viability. Adding the viability caveat is only sensible in light of a momentary understanding of “undue burden.”

Furthermore, Girgis recognizes that any ban before viability always constitutes an undue burden under Casey. This is seen here in another quote from Casey:

“Before viability, the State’s interests are not strong enough to support a prohibition of abortion or the imposition of a substantial obstacle to the woman’s effective right to elect the procedure.”

And what is at issue in Dobbs is precisely that: a prohibition on abortion. Casey expressly forbids what some are trying to use Casey to defend. That is not how stare decisis works. Respecting precedent does not require twisting a prior decision into a confusing pretzel of incognizable rubbish. As Chief Justice John Roberts noted, “stare decisis is a doctrine of preservation, not transformation.” One should not “radically re-conceptualize [a prior decision’s]reasoning.”

Ironically, Chief Justice John Roberts is most likely to take this middle-ground approach, which requires one to re-conceptualize Casey’s momentary undue burden standard into something altogether different. In the Dobbs oral argument, Chief Justice Roberts was the only one proposing this outcome. The other conservatives were largely skeptical of calls to stare decisis. As shown above, respect for precedent is a flimsy legal ground for upholding Mississippi’s 15-week ban.

Of course, SCOTUS is not guaranteed to reverse Roe. They could opt for a middle ground approach, sacrificing legal cogency for political palatability. They’ve stretched the imagination before—just look at Roe and Casey. But an airtight decision will mean Roe is gone. Anything less will present the Pro-Life movement with a fat and feeble target for our next round of Pro-Life bills.